Inclusive Language

Language is a powerful tool for fostering inclusive study and work environments where everyone feels they belong. Inclusive language is not a trend or about being ‘politically correct’, rather it is about ensuring that everyone feels welcomed, valued and respected in all communications, interactions and spaces.

It’s no surprise that organisations are developing inclusive language guides as a key strategy in setting the tone for creating and maintaining an inclusive culture.

In education and training, inclusive teaching should include inclusive language because at the heart of teaching and learning is the individual. Using inclusive language in academic writing and learning activities also fosters graduates with inclusive graduate capabilities.

Why inclusive language matters

Words can empower. An inclusive culture which includes a strategy to embed inclusive language has a range of positive benefits to your organisation.

Inclusive language can:

- improve whole-of-institution strategy which supports diversity and inclusion

- build capacity in your workforce around inclusion and meet relevant performance indicators

- enrich teaching and learning elements e.g., curriculum, assessment, work-integrated learning, research

- enhance graduate capabilities or employability skills to improve employment outcomes for students.

Words can also hurt. Work undertaken by organisations such as the Australian Human Rights Commission, the Diversity Council of Australia, and the Australian Institute for Health and Welfare shows that non-inclusive language can have a range of negative impacts on people and organisations.

Non-inclusive language can:

- contribute to and perpetuate stereotypes and lead to harassment, discrimination, vilification and in some cases violence (e.g., sexist and racist language, homophobia, transphobia, ableist language, gendered violence)

- harm not only individuals but those who witness non-inclusive language

- cause individuals to be othered or marginalised

- diminish people’s sense of belonging and reduce their contributions within a study environment or workplace

- lead to poor mental or physical health outcomes

- result in absenteeism, poor productivity or leaving an organisation for staff

- can result in poor performance, absenteeism or attrition for students in education or training

- lead to harassment, discrimination or vilification which is unlawful and can lead to formal complaints or criminal prosecution. These incidents can not only impact complainants and respondents but are costly to individuals and organisations and can result in legal and criminal penalties, vicarious liability, and reputational damage to organisations.

Fostering diversity and inclusion

As part of developing a diverse and inclusive work and study environment developing inclusive language is essential. People should be able to bring their whole self to their study or work environment, so words matter.

Inclusion and diversity means recognising, respecting and valuing individual differences, and having an environment where people are empowered and can fully contribute their talents, skills, experiences, thoughts and energies to the workplace. It involves removing barriers to ensure everyone is able to participate and have equal access to opportunities. It enables new and innovative ways to work, solve problems and create efficiencies and quality outcomes for the benefit of the organisation.

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Inclusion and Diversity Strategy, 2018-21

When you leave out members of the work or study environment you deny their full participation and contribution. Humans are complex beings with their own unique identities who bring valuable perspectives, contributions, and ideas to an organisation (see Figure 1). Consulting with people with lived experience and expertise is vital in creating an inclusive work and study environments.

Dimensions of diversity and identity include:

- Aboriginality

- ability

- gender and gender diversity

- sex

- sexuality

- race and ethnicity

- nationality

- migration experience

- language

- religion and belief

- age

- mental health

- socioeconomic status

Figure 1: Dimensions of diversity and identity

Intersectionality

The overlap of these characteristics represents the complex dimensions of the human experience, but also how attitudes, systems and structures in society and organisations can interact to create inequality, exclusion and discrimination. This includes sexism, racism, homophobia, ableism, and ageism. The concept of intersectionality has developed to explain how different aspects of a person’s identity can expose them to cumulative or overlapping forms of discrimination and marginalisation.

Acknowledging intersectionality also means recognising that people are not confined to one identity and that individuals have multiple facets and identities. Interacting with people using an intersectional lens or approach improves the way we interact and communicate with others. Language is a central part of those interactions.

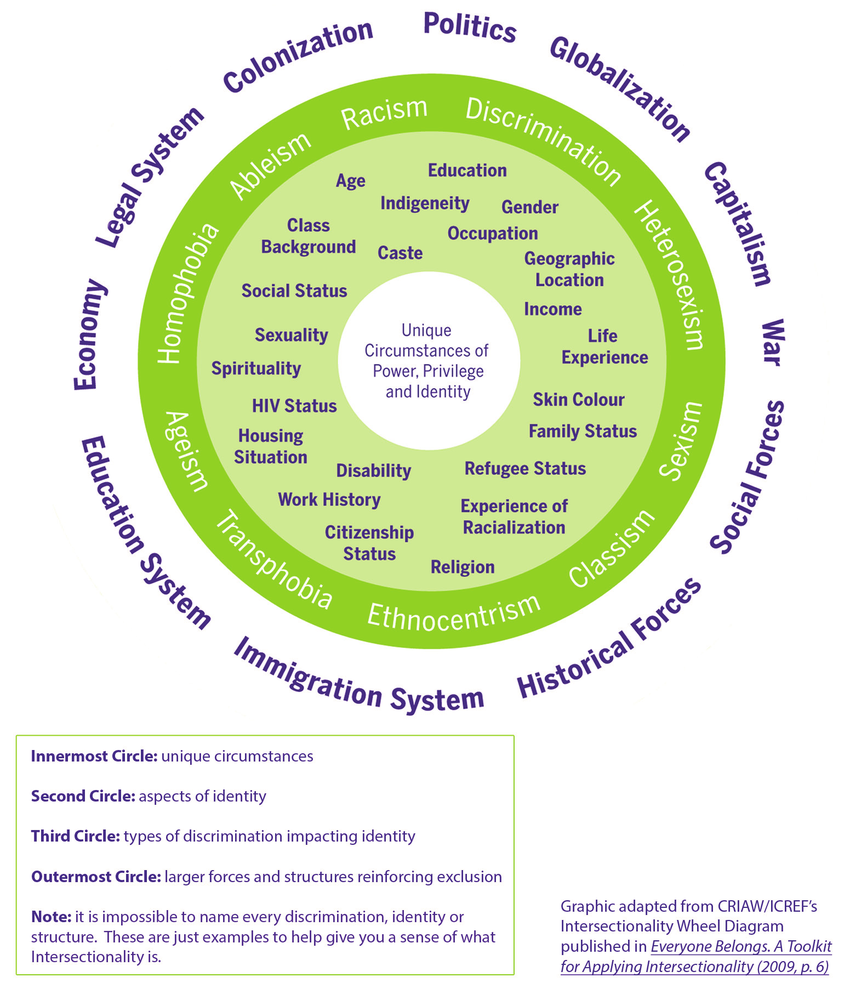

The diagram (Figure 2) below taken from Everyone Belongs: A Toolkit for Applying Intersectionality ![]() by the Canadian Institute for the Advancement of Women illustrates multiple layers of power, oppression and discrimination experienced by people. It is also a way to look at identity, relationships and the way people move in the world.

by the Canadian Institute for the Advancement of Women illustrates multiple layers of power, oppression and discrimination experienced by people. It is also a way to look at identity, relationships and the way people move in the world.

In the intersectionality wheel there are four layers:

- the centre illustrates the unique circumstances of power, privilege and identity

- the second layer is the multiple identities individuals possess such as disability, age, gender, race, sexual identity, class, location etc.

- the third layer shows the types of discrimination or marginalisation that impact identity e.g., racism, homophobia, ableism etc.

- the final layer is the larger forces and structures reinforcing exclusion such as colonisation, capitalism, economic participation, education etc.

Figure 2: Intersectionality wheel

Five steps to inclusive language

The Diversity Council of Australia ![]() developed Words at Work to talk about developing inclusive language in workspaces but it relevant to learning and teaching spaces as well.

developed Words at Work to talk about developing inclusive language in workspaces but it relevant to learning and teaching spaces as well.

1. Person-centred language

Focus on the individual, rather than their demographic group. While we might collectively 'people with disability' as a group we need to note that within this group individuals have unique identities and experiences. This is not to say you should ignore their identities but ask yourself is it relevant to situation. For example, when introducing people.

Instead of: “Hi everyone, I want to introduce you to Rob, he is new to our teaching team and has Autism.”

Try: “Hi everyone, I want to introduce Rob, he is new to our teaching team and has expertise in inclusive teaching techniques for Autistic people. Rob is happy for me to also share with you that he is Autistic.”

Instead of: “Hi team, just letting you know that one of our students is transitioning from male to female.”

Try: “Hi team, I am calling a meeting to talk confidentially with you about one of our students who is affirming their gender. The student and their support person have sent us with some resources so we can provide the appropriate support during the gender affirmation process including affirming their name and pronouns.”

2. Context matters

Language that may be fine outside of work can be non-inclusive at work. Sometimes people use terms about themselves or their friends or ‘in group’ that are not appropriate for others to use about someone in a work context. This is particularly the case for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, people with disability and LGBTIQA+ communities who have a range of terms they use for themselves but should not be used by people outside these groups. Language is constantly evolving so keeping abreast of these changes within the relevant communities is also important.

3. If in doubt, ask.

This is good advice for both working with individuals and when working with groups. Check with individuals about how they wish to be introduced or referred to. This includes affirmed / preferred name, titles, pronouns, nicknames, membership to a group.

Instead of: “Jen is here today to talk about her research, please welcome her.”

Try: “Dr Jennifer Smith is here today to talk about their research in Queer pedagogy, please welcome them.”

Language is constantly evolving so it is useful to seek advice from relevant organisations e.g., disability networks such as Australian Disability Network, Pride in Diversity, etc.

4. Keep an open mind

Be open to learning about respectful and appropriate language. We know there is language and terminology that we wouldn’t think of using now that was commonplace in the past. So, recognising our own unconscious bias is important. Be open to learning from others with more expertise, those with lived experience, considering other perspectives, and recognising you don’t have all the answers.

5. Keep calm and respond

If you are called out, or if you want to call out exclusionary language, be calm and respond appropriately. Don’t get defensive, take it as a learning experience.

Instead of: “Can’t you take a joke?”

Try: “I am sorry I didn’t mean to offend you.”

Active bystanders can be great allies in improving organisational culture so don’t be afraid to speak up but consider how you approach your intervention. For example, calling someone out in public or pulling them aside. Some examples include:

- “I don’t think that is an appropriate way to talk about people with disability.”

- “That’s a really demeaning way to talk about women…do you really feel that way?”

- “I don’t think this conversation is very positive so let’s stop there.”

Developing an inclusive language guide

Many education providers have developed their own inclusive language guide or are considering one. For example, a stand-alone guide, a style manual or inclusive teaching tool.

Here are some tips for developing a guide:

- consider the purpose for your guide. It should be one of the key strategies of your organisation’s diversity and inclusion objectives

- consider the organisational areas to consult with. Your consultation should encompass people with lived experience and expertise from the relevant communities including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives, people with disability, LGBTIQA+ communities and other under-represented groups. You should also include student and staff equity representatives, student support services, teaching and learning, marketing and recruitment, policy and governance, human resources, student advocates who work closely with diverse groups and communities. Include these groups in the development of your guide so it works effectively across all parts of the organisation and the diverse communities that engage in your organisation

- seek our staff and students with expertise and lived experience

- ensure it is produced as a living document that evolves with changes in language

- consider drawing on expertise from key advocacy groups you might already be partnering with such as Pride in Diversity, Australian Disability Network, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community partners

- look at other existing inclusive language guides for guidance (be sure to reference them appropriately)

- make sure your guide is accessible and easy to find for staff and students

Here's something we prepared earlier!

Developing a guide to inclusive communication: a resource for tertiary education providers is a blueprint for developing inclusive communication for your organisation which encompasses inclusive language and visual representation.

Further resources

References

Diversity Council of Australia (2016). Words At Work: Building Inclusion Through the Power of Language, Sydney.

AIHW: People with disability in Australia 2020: in brief, Discrimination

AHRC: Workplace bullying: Violence, Harassment and Bullying Fact sheet

(April 2023)